|

| M. de Garsault, Art du Tailleur (1769), plate 12 (detail). Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF. |

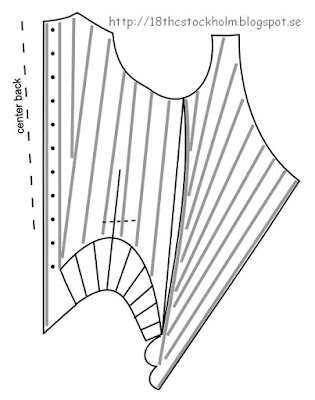

Garsault doesn't depict individual pattern pieces, but we can use his illustrations and written information to alter another pattern into his cut.

Pattern characteristics

The main features are these:- There are just three pattern pieces, according to Garsault.

- The side seam runs diagonally from armscye to front point.

- A gusset is inserted at the side back (technically it's a 4th pattern piece, but for some reason Garsault doesn't count it as that).

|

| M. de Garsault, Art du Tailleur (1769), plate 12, figure 4. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF. |

This figure also shows the side seam. It starts roughly at the bottom of the armscye, and ends at the side of the broad point in the front.

Notice also how long and finger-like the tabs are. They're almost like narrow pie slices, all cut from a small, curved, area. Many French stays and court bodices from the first half of the 18th century have this kind of tabs.

If you'd like better resolution pictures, please visit Bunka Gauken (they are very restrictive about reuse, though).

The gusset

|

| M. de Garsault, Art du Tailleur (1769), plate 12, figure 2. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF. |

The placement of the gusset is shown on a pair of fully boned stays (plate 12, figure 2, letter c). Note the horizontal line above the 'c', which shows how far upwards the gusset will extend. Similar gussets are seen in some extant stays. (Diderot has copied Garsault's illustrations, but omitted the letters in his corresponding illustration, so it's not clear whether Diderot's stays would've had gussets or not.)

Garsault also mentions the gussets in the text. The waist should be cut "two fingers narrower than the measure, because you will then put a gusset or widening on the hips, to give them play, and prevent the body from hurting in this place; this widening will regain what you have cut off from the measure, and it is all the more necessary, since the hips of women are almost always larger than those of men." (page 41, translation by Google Translate). I.e., at the waist you take away a little from the squishy areas and use it to reduce pressure on the lower back.

He doesn't discuss the shape of the gussets, but the above quote implies that they are necessary for women's hips, which suggests that the gussets widen over the hip, before the start of the tabs. Gussets in extant stays have a narrow triangular shape from the waist up, but from the waist down they quickly become wider, usually ending in two tabs. In the rare cases where I've spotted gussets in court bodices (which have tabs starting at the waistline), the gusset is just a skinny triangle inserted from the waist and up.

The gussets are mentioned again on page 42, after the corset has been boned, assembled and fitted—he says that after fitting, you bone the gussets. I take this to mean that the gussets may need to be adjusted as part of the fitting, likely to get the hip curve right, and therefore aren't boned until afterwards.

|

| Detail of circa 1730-1740 stays, LACMA M.57.24.1 |

An extant pair of Garsault-like stays

Queen Sophia Magdalena of Sweden had a pair of half-boned stays that is remarkably similar to Garsault's plates. She was a princess from Denmark, born in 1746, married crown prince Gustav of Sweden (later king Gustav III) in 1766 and died in 1813. The stays have been passed down in the family of her lady-in-waiting, Brita Sophia Grahn née Hallström. (There's no dating for the stays, nor have I found out which years Brita Sophia had the position of lady-in-waiting.) The queen's stays have a 54 cm (21 1/4") waist.| Queen Sophia Magdalena's stays. Source: Sörmlands museum |

M. de Garsault, Art du Tailleur (1769), plate 12, figure 2. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF. |

Although the over-all shape and cut is very similar, the side by side comparison shows that the front/back proportions are a bit different (here, both images are scaled to the same height). The back of Garsault's stays is depicted way too narrow, while the front is quite similar to the queen's stays.

In the photo, the light comes from the right-hand side, and the silk at the side of the bust doesn't reflect as much light as the rest does, suggesting that the garment is curving slightly towards the camera in that area. Therefore I think the side edge of the front piece is slightly shaped. A front piece with a shaped edge to the side seems to be a standard feature in stays in the 2nd half of the 18th century, although Garsault doesn't mention it.

Close to the the back lacing there seems to be second, shorter, gusset, or perhaps a shaped side back seam that gives extra width from the waist down.

I'm glad the museum chose to photograph the stays folded flat like this, as it made the similarities to Garsault's design very obvious.

Altering a pattern

Garsault doesn't give drafting instructions, but if you have a pattern that fits it's easy to alter it to Garsault's cut. The dividing seams in the back and side should be straight; e.g. you could use a pattern based on Waugh's "Diderot pattern". If seam lines aren't drawn in, do so now, and mark the waist along the seamline.Garsault subtracts "two fingers" from the waist measurement to allow for the gussets. I take it that he subtracts it from the entire waist, so "one finger" from each side. I suggest "one finger" is 1.5 to 2 cm (5/8" to 3/4"); decide which measurement you want to use. It will be used both in altering your stays pattern, and in constructing the gusset pattern.

Overlap the pattern pieces, matching the seamlines at the top edge and waistline (this may cause them to overlap below the waist). At (or near) the side, you overlap the seamlines by "one finger" at the waistline (they should still touch at the top edge). Compare the general shape to my sketch below.

Now that you've established the shape of the pattern pieces, here are some further hints:

- Garsault's stays have a converging lacing gap at the center back (see pic and measurements in Continental stays 1: Diderot à la Waugh). Without it (or with a parallel gap), the boning pattern might look different.

- Back boning: first draft the parallel boning to the sides of the lacing holes. Next, one strip runs from the middle of the shoulder to the waist or lower back. Fill in with more parallel lines of boning up to the gusset slit.

- Side boning: all boning between the slit and the side/front seam is parallel to that seam.

- Front boning: one strip runs along the curved edge of the dividing seam. The strips closest to the center front seem to converge slightly downwards. To draw in the rest of the strips, I found a neat trick when I was analyzing Garsault's drawing. First decide where the boning's top ends will go. Then you decide on the direction on the leftmost and rightmost strip, extend both of these downwards until they cross, and draw straight lines between that point and each of the marks in the top. (I.e., you do e.g. all the left sides of the channels in this way, and then you draw in the right sides to be parallel.)

- The gusset slit is perpendicular to the base of the tabs, and continues straight into the tabs.

- Do as many or as few tabs as you need to retain the proportions. I suggest you continue the boning lines into the tabs as far as they will go. Add more, short, bones to the tabs as needed (like in other half-boned stays patterns).

- Transfer the front and back pieces onto separate pieces of paper, add seam allowances and cut out. The center front and the almost-center-back edge should be placed on the straight of grain. You'll also need the shoulder strap piece from the pattern you started with.

- Finally, it's time to draft the gusset!

Drafting the gusset

|

| Gusset for Garsault stays (not to scale). |

Garsault doesn't tell us how to draft the gusset, so this is mainly based on what I've gleaned from photos etc. My schematic sketch above shows the gusset slit, and the gusset. The gray area corresponds to the upper part of the opened slit; the width at the waist should be "one finger" as above. The height of the gray area matches the distance from the waistline to the top of the slit. To the left and right sides of this triangle I added one seam allowance, that corresponds to the distance from the slit to the seamline. Then I added another seam allowance, which is the actual seam allowance of the gusset. Use narrow seam allowances, say 7 to 10 mm (1/4" to 3/8").

Below the waistline, the gusset curves out to allow for hip spring. Experiment to see which shape works for you! The larger the hip spring, the wider and shorter the curved section will be. (In the blue stays above, most of the hip shaping is in other seams, with only a little in the gusset.) Mark the waistline and the beginning of the tabs on the stays and gusset, as they need to match.

The seam allowances of one gusset piece are folded under, and the gusset is placed on the outside and topstitched in place (the top edges can be hemmed down). A corresponding piece is added to the inside. Garsault says the gussets are boned after fitting.

Conclusion

In Garsault's stays pattern, there's a single back/side piece, with the gusset providing all of the hip shaping. Garsault's seamlines are more sensibly placed than in Diderot's pattern, which makes for a better fit in the bust and lower back. It is an unusual cut, yet it's closely related to other Continental patterns—I will discuss one such pattern in part 3 eventually.Also, Garsault's pattern might be viewed as an ancestor of J.S. Bernhardt's single-piece stays pattern published in 1811 (now famous thanks to Sabine's Short Stays Studies). Bernhardt took things even further by incorporating the front piece too, and using more gussets.

No comments:

Post a Comment